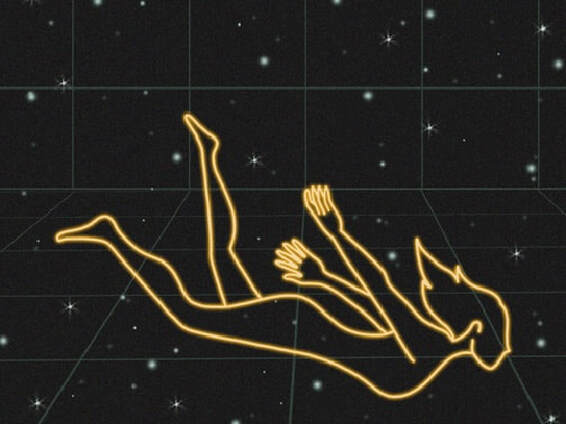

GRAVITY

Photo Courtesy of Across the Margin

A literary journal called Across the Margin just published my short story, Gravity. You can read it down below. However, the journal is so interesting and the graphics are so cool, I suggest you take a look at it online.

***

Marilyn’s last sight before dropping dead on the steaming hot asphalt was three black turkey vultures circling overhead in the cerulean sky.

She hadn’t expected to die that afternoon. Moments before as she trudged home after a day at work, she’d been thinking about the evening that lay ahead. She planned to watch the 6 o’clock news while she ate her organic brown rice and chicken tenders, purchased from Trader Joe’s. Then she’d make a cup of Good Earth tea and read a few pages of the latest National Geographic Magazine. She’d get into bed at 8:55. She used to have to let the cat in at night and then go to bed at 9:00, but Mika had died the year before. She wondered if the gray tabby were in cat heaven. That’s when she looked up and saw the turkey vultures.

A second later, she felt a jolt of chest pain, followed by a sensation that she later described as “all gray and melting into the pavement.”

Next, Marilyn seemed to be hovering over her own body, which lay crumpled in the roadside. She had fallen in an unattractive way. Rump up, legs akimbo. She wished she’d taken that Step Class at the gym. Wouldn’t it have been nice to have had a firmer behind?

She also hoped that a kind neighbor would find her and not a reporter with a camera. She didn’t want her back end to grace the front page of the local newspaper.

To be honest, thirty-eight-year old Marilyn had always lived in fear of dying a ridiculous death. She worked for the government, tracking national morbidity and mortality. At monthly staff meetings, she’d provide anecdotal data to her colleagues, whose job it was to spot trends. She’d read her reports in a straightforward manner, but before she knew it, the room would erupt in laughter. The analysts would find humor in the most awful events—a prisoner struck by lightning while sitting on a toilet, a factory worker drowning in a barrel of pickles, a secretary getting her neck crushed in elevator doors during a power outage. Their reactions mystified her.

Images of these unintended deaths kept her up at night. And, as she lay awake, losing sleep, she’d remember a study that claimed insomniacs died at a younger age than those who were blessed with a good night’s rest.

All those worries were for naught now that she appeared to be dead. She saw with horror that the turkey vultures were circling lower in the sky. Were those birds prescient? Had they been following her, just waiting for her to tumble? Years ago, Marilyn had read that these ugly profiteers of nature knew when a creature had died because they could sense whether oxygen flowed through the being.

In life, Marilyn’s head had been stuffed with disturbing facts, which she tended to blurt out when she felt anxious at social events. People hated to sit next to her. Out of the blue, she’d look at a bookcase and start talking about how last week a toddler had pulled a three-shelved one onto his head. Crushed him. Resuscitation proved ineffective. Or, she’d mention that a teen walking through a friend’s kitchen collapsed and died because the vegetarian mother was making chickpea soup. The teen happened to be highly allergic to chickpea fumes. Who knew? Who could have ever guessed? Marilyn viewed the world as being filled with landmines.

All this is to say that people tended to avoid Marilyn, which confused her. Didn’t they want to be safe? Didn’t they want to know how to survive?

Now Marilyn wondered if anyone would be at her funeral. Would she be there? Yes, her deceased body would be present, but would her spirit be floating above observing the event? If nobody came, she wouldn’t want to see that. Too painful. If people attended but didn’t seem to be all that overwrought, that also would hurt.

It would be nice if at least one person were devastated by grief. She couldn’t think of anyone who would even come close to being devastated. Mother and Father gone. No siblings. No other family to speak of. A few co-workers, mostly introverted number-crunchers. Her neighbors? Maybe they’d be at the funeral.

She pictured her next-door neighbor, Najib, a cartographer who worked for the national parks. A few times in the past year, he’d lean over the fence that divided their backyards and ask, “Marilyn, any time you want to go out for ice cream, just let me know.” Marilyn would smile but say nothing. She needed to avoid ice cream because of her lactose intolerance. If he had asked her to go out for coffee and doughnuts, she would have said yes in a heartbeat, but he never did. Maybe she should have mentioned doughnuts to Najib. Why didn’t she? She just plain hadn’t thought of it. Too late now.

She hadn’t ever dated anybody except for that one awful evening with the skinny guy in accounting who talked non-stop about his last girlfriend. While they sat a small table at a dingy restaurant, the man kept touching her hand to emphasize any point he made. Marilyn found this disgusting. Who would want to touch another person’s germy hand before eating? Tears welled up in his eyes while he spoke. Marilyn couldn’t decipher if he was angry or sad. A sad face and an angry face looked about the same to her, which often got her into trouble. At the end of the evening, he stuck her for the whole tab. The accountant never asked her out again and in fact, hardly ever acknowledged her presence at work.

Marilyn looked down at her body. The birds seemed to be swooping even closer. Wait. Was that a car coming down the road?

All at once, Marilyn felt engulfed by, no, embraced bya bright shimmering yellow glow, above her, below her, all around her.

Silence. Peace, a peace that overwhelmed every bit of Marilyn, so much so that she no longer felt her distinct Marilyn-ness.

“Can you hear me? Can you tell me your name?” Marilyn heard shouting from a great distance. “Do you know where you are?”

Marilyn tried to open her eyes. Was that a woman in green scrubs? The white glare of a fluorescent light assaulted her eyes. She closed them again. Marilyn tried to form words. None came.

“Tell me your name.”

Name? Jumbled thoughts: Vultures flying overhead. Sun. Blue sky. Good Earth tea. Asphalt.

“Marilyn. Your name is Marilyn. How about the day? What day is it?”

“Marilyn….” Slowly, Marilyn remembered the jolt of pain. She tried to sit up. No dice.

Her chest felt as if a horse had kicked it. Wires and tubes everywhere. Marilyn tried to say, “Tuesday.”

“What’s that honey?” Green scrubs asked.

Marilyn said, “Tuesday.” Clearer this time.

“That’s right. Good for you.” Green scrubs leaned in, “You are at Mercy General. You had a heart attack. On the road. While walking. Do you understand?”

No, Marilyn did not understand. She was a non-smoking, young woman in decent health, for goodness sake. She shook her head “No.”

“Two lifeguards, teens really, found you. On their way to Washington Park, to work. They did CPR. Brought you back to life. Called an ambulance.” Green scrubs smiled. “You are a lucky woman.”

Marilyn did not feel lucky.

After Marilyn fell back to earth, the world looked different. On her first trip to the grocery store after her hospital stay, she bought a mango. All her life, she’d seen mangoes on the shelf, but had never tasted one. At home, she peeled the fruit then shaved off little pieces. The flavor surprised her, all at once sweet and tangy, not at all like a cantaloupe whose color was similar, but differed in taste and texture. She spooned out a few dollops of yogurt, added the mango bits and a handful of cashew nuts. Marilyn brought the bowl to her back porch where she settled into a rocking chair. As she ate slowly, she watched a bird build a nest in the hemlock behind her house. She breathed deeply, taking in both fragrance of honeysuckle and the smell of wood smoke from a Najib’s grill.

She did not go back to work. She could not imagine facing morbidity and mortality data every day. So, she quit. Not only did she quit, she did something utterly uncharacteristic of her. She quit before she had any idea what she’d do next.

A month after her hospitalization, Marilyn waited in her cardiologist’s office. His appointments always ran behind. Already forty-three minutes and thirty-five seconds late today. She sat with her back straight on a maroon leather chair so slippery she had to hold onto the side arms to avoid sliding onto the beige rug. To pass the time, she picked up a glossy tourist magazine, one with gorgeous full color photos, but hardly any content. Normally, this content-free magazine annoyed Marilyn, but today she relaxed into the beautiful shots of gazebos, blue-green mountains, honeybees hovering by brilliant blossoms. As she paged through the issue, she landed on an article about a new sky diving enterprise located in a town near the Blue Ridge Mountains. One photo reminded her of the aerial view of her neighborhood she’d seen while her heart quit on her.

After Dr. Bausch examined her and reviewed her test results, he said, “For a woman who’s just had a major heart attack, you’re looking pretty good.”

“Pretty good? How good is that?” Marilyn wanted numbers from the man, predictive statistics.

The doctor took off his glasses and absently chewed on an earpiece. Marilyn didn’t like the pause. He seemed to be choosing his words too carefully.

“Well, Marilyn, you had a ninety percent blockage in one artery and seventy-five percent in another artery. You are now the proud recipient of two stents. Your heart doesn’t have to work as hard as it did…”

That didn’t sound as comforting as Marilyn hoped. “So, I don’t need to worry about having another heart attack….”

Dr. Bausch slid his glasses back on. He tapped his pen against her chart and before he could start another stalling activity, Marilyn leaned forward and said, “Just tell me, for god’s sake!”

“Your heart sustained a fair amount of muscle damage. The stents will relieve symptoms—pain and chest heaviness, but they won’t necessarily prevent another heart attack.”

Marilyn slumped into her chair.

“Marilyn. I’ve observed you these past weeks. I’m confident you’re going to be diligent about self-care; you’re going to eat well and exercise.”

Marilyn felt tears spill down her cheeks.

Dr. Bausch leaned forward and touched her arm. “Regardless, the answer to your question is that you don’tneedto worry. Worrying won’t help.” He paused then said, “You’re going to do your best. I’m going to do my best. You could live a very long time.”

Two Weeks Later

The navy-blue jumpsuit felt big on Marilyn. She had trouble negotiating the stairs up onto the small plane. Luc, her instructor, climbed right behind her. As she stumbled up the third step, he cupped her elbow, steadying her. On a bench inside the cabin, three men sat, laughing and talking about the Red Sox over the loud whir of the plane engine. They each would dive solo, followed by Luc and Marilyn in tandem.

In the hangar, two hours before, during a surprisingly brief training session, Luc had gone over every aspect of the dive, the order of events, hand signals he would use, the way she should position herself during each phase of the dive. Marilyn found Luc’s Swiss-German accent mesmerizing. He exuded confidence and warmth. A compact, muscular man, he had been skydiving for twenty years in the Alps. He planned to stay in the US only a year or so to help launch this Virginia company. On the ground, when handed Marilyn her altimeter, he said, “We will ascend to fourteen thousand feet in the airplane. Miles above terra firma. Thrilling, yes?”

Now, as Marilyn settled on the hard bench next to the three loud men, she didn’t feel thrilled. Her tongue stuck to the roof of her dry mouth. Her saliva tasted metallic. Her forehead and jaw ached. Cold sweat collected on the palms of her hands. Her stomach churned. Her two legs felt leaden, somehow rooted to the floor of the plane.

Luc whisper-shouted into her ear, “Deep slow breaths, Marilyn,” pronouncing it ‘Mare—ee—leen.’

But her breaths remained short and shallow, no matter how hard she tried to slow them. More alarming, though, was how hard and fast her heart galloped in her chest. She had lied on the waiver. Health problems? She checked, “None.” Normally, she would never consider lying. Facts are facts, after all. However, she decided the reason the company asked the question was because they didn’t want to get sued. She’d felt a twinge of guilt; however, another set of facts emerged and took precedence. She thought, I have no husband, no parents, no siblings. If anything goes awry, no one will be suing the company.

Luc tugged on her sleeve then pointed out of the small window. “How high do you think we are?”

Marilyn craned her neck and peered down to see an asphalt ribbon of a road with ant-sized cars on it. “Twelve thousand?”

“Ha! Only five.” He smiled and pointed up. “We are ascending into the heavens!”

Later, after some signal that Marilyn missed, the three men stood in unison and lined up by the door, each adjusting his harness. Another instructor opened the door. One by one, the men seemed to be sucked out of the plane.

Luc gestured for Marilyn to stand. She shook her head no, but he guided her to her feet. She stood in front of him as he fastened the tandem harness, joining the two of them, his arms and legs behind her shoulders and back. Before she knew it, Luc had pushed the two of them out of the plane.

Free fall.

Cold air.

The roar of the plane fading into the loud whoosh of the wind.

The feeling of that brisk wind pressing against her face.

Luc’s arms and legs cradled her. What might have it been like to spoon in bed with a husband on a lazy Sunday morning?

Free fall. Then arms and legs akimbo, facing earth from fourteen thousand feet above, they fell at one hundred-and-twenty miles per hour.

She didn’t experience a dropping sensation. Instead, she felt as if she were blissfully floating. And as she floated, she seemed to shed her fears and worries about health, death, finances and all manner of regrets. She felt bathed in an abiding peace that her soul welcomed and her mind struggled to comprehend.

She looked down to see her earth, her world, filled with a shifting mosaic of color and shapes. The sixty seconds of free fall felt like a delicious eternity. All at once, Marilyn experienced the world as much bigger and more beautiful than she’d ever imagined but also much more intimate and comforting than she’d ever felt.

Luc touched her shoulder then made a hand sign. She checked her altimeter—six thousand feet. Time to open the parachute. As she’d been instructed, she placed her hands below her shoulders then gripped her harness. As the parachute deployed, she felt a forceful tug upward and a slight pain in her hips.

Then they floated, leisurely, luxuriously soaking in time and space. As they drifted downward, the brilliant mosaic of shapes and colors rearranged themselves into specific mountains, roads, trees and buildings. Marilyn felt both deeply calm and deeply thrilled. The da Vinci quote she’d read on the skydiving brochure came to mind, “For once you have tasted flightyou will walk the earth with your eyes turned skywards, for there you have been and there you will long to return.”

Luc tapped her right shoulder then made the sign for landing. Marilyn tucked her knees above her hips. They hit the grass with a bump and a roll. Marilyn shook free of her harness and stepped out onto a new earth.