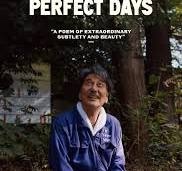

PODCAST-MOVIE REVIEW-PERFECT DAYS

Recently, I watched Perfect Days. Released in 2023, it’s a film directed by Wim Winders. I’ll have to admit, I had a hard time sitting through the first hour of this movie, but then it grew on me.

On the surface, nothing much happens. We follow Hirayama (played by Koji Yakusho) through each of his days, one after the other. He wakes up in a small room that contains little other than a row of books neatly stacked on the floor along the perimeter. He washes and shaves, climbs to a small attic and mists tree seedlings growing under a light. Then he gathers several sets of keys which are kept in an orderly row on a shelf by his doorway.

As he steps out of his door into a grimy urban setting, he gazes at the skyline where he can see a tree in the distance. He beams at the sight. Hirayama buys coffee at a vending machine, then starts his day cleaning the public toilets of Tokyo. He approaches the task with respect and dedication, at the ending of each cleaning, using a mirror to check the underside of every surface.

Hirayama sees the same people every day—an unhoused person who camps under a tree, a young woman who eats lunch on a bench adjacent to the bench where Hirayama pauses for lunch. The two sit silently and look at the same tree as they eat. Before leaving, Hirayama always takes a photo of the tree. Later, he grabs a beer at a bar where every evening the server brings out the beverage with great gusto, proclaiming, “For all your hard work!” Then Hirayama heads to a restaurant owned by a woman named Mama. Even though Hirayama and Mama keep their conversation to a minimum, their facial expressions and body language reveal that the two have strong feelings for each other. Hirayama’s day always ends the same way: he rolls out his sleeping mat, then reads. When he closes the book, we can see that it is a William Faulkner novel. He turns off his light, and dreams. Each night Hirayama’s dream sequences are portrayed, some seeming to incorporate bits of his day.

Winders takes his time establishing Hirayama’s routine before introducing a couple of blips in the plot line. Hirayama’s unscrupulous assistant borrows money from him, steals one of his precious music tapes, then quits unexpectedly, leaving Hirayama in the lurch. This bumps up the narrative tension a tad. How he handles the situation reveals both Hirayama’s values and how he manages conflict.

Hirayama’s teenage niece, Niko, runs away from home then shows up at Hirayama’s apartment. It’s been so long since he’s seen her, he doesn’t recognize her at first. For a few days, Niko shadows him as he works on the toilets of Tokyo. Neither one judges the other. When Hirayama takes his daily picture of that tree. Niko pulls out an identical camera, one that he gave her years ago. Ultimately, something happens with Niko that reveals some of Hirayama’s complex backstory. For the first time, we see him weeping.

In another scene, Hirayama is approaching Mama’s restaurant. Through the large window, he sees Mama hugging another man. Distraught, he heads to the river and smokes a cigarette. I don’t want to reveal too much, but what happens next is quite moving. After feeling as if I’d been Hirayama’s close companion for many days, I resonated with the character and experienced those emotions alongside him. The last few minutes of the movie brought me to tears—a testament to Koji Yakusho’s phenomenal acting and Wim Winder’s nuanced directing.

The lush and soulful soundtrack adds an engaging texture to this film. Hirayama owns a collection of old cassette tapes and plays one on his way to work each morning. The film’s title comes from the Lou Reed song, Perfect Day. He listens to other classics such as Van Morrison’s Brown-eyed Girl and Nina Simone’s Feeling Good. This Faulkner-reading guy who listens to American classics erases any stereotypical view you may have had regarding people who clean toilets for a living.

Once I relaxed into the rhythm of the film, I became thoroughly engaged by the great acting, gorgeous cinematography, and the moving soundtrack. Most of all, the central message of the movie has had a lasting effect on me: to be happy with what is given to you.

Almost daily, I’ve been reminded of the film. I think of a line, an image, a bit of dialogue, and especially Hirayama’s joyful embrace of mundane aspects of his life. Originally, Wim Winders intended to make a documentary about the splendid and innovative public toilets of Japan, but somewhere along the line, he decided to create this film instead. I am very glad that he did.

Recently, I watched Perfect Days. Released in 2023, it’s a film directed by Wim Wenders. I’ll have to admit, I had a hard time sitting through the first hour of this movie, but then it grew on me.

On the surface, nothing much happens. We follow Hirayama (played by Koji Yakusho) through each of his days, one after the other. He wakes up in a small room that contains little other than a row of books neatly stacked on the floor along the perimeter. He washes and shaves, climbs to a small attic and mists tree seedlings growing under a light. Then he gathers several sets of keys which are kept in an orderly row on a shelf by his doorway.

As he steps out of his door into a grimy urban setting, he gazes at the skyline where he can see a tree in the distance. He beams at the sight. Hirayama buys coffee at a vending machine, then starts his day cleaning the public toilets of Tokyo. He approaches the task with respect and dedication, at the ending of each cleaning, using a mirror to check the underside of every surface.

Hirayama sees the same people every day—an unhoused person who camps under a tree, a young woman who eats lunch on a bench adjacent to the bench where Hirayama pauses for lunch. The two sit silently and look at the same tree as they eat. Before leaving, Hirayama always takes a photo of the tree. Later, he grabs a beer at a bar where every evening the server brings out the beverage with great gusto, proclaiming, “For all your hard work!” Then Hirayama heads to a restaurant owned by a woman named Mama. Even though Hirayama and Mama keep their conversation to a minimum, their facial expressions and body language reveal that the two have strong feelings for each other. Hirayama’s day always ends the same way: he rolls out his sleeping mat, then reads. When he closes the book, we can see that it is a William Faulkner novel. He turns off his light, and dreams. Each night Hirayama’s dream sequences are portrayed, some seeming to incorporate bits of his day.

Winders takes his time establishing Hirayama’s routine before introducing a couple of blips in the plot line. Hirayama’s unscrupulous assistant borrows money from him, steals one of his precious music tapes, then quits unexpectedly, leaving Hirayama in the lurch. This bumps up the narrative tension a tad. How he handles the situation reveals both Hirayama’s values and how he manages conflict.

Hirayama’s teenage niece, Niko, runs away from home then shows up at Hirayama’s apartment. It’s been so long since he’s seen her, he doesn’t recognize her at first. For a few days, Niko shadows him as he works on the toilets of Tokyo. Neither one judges the other. When Hirayama takes his daily picture of that tree. Niko pulls out an identical camera, one that he gave her years ago. Ultimately, something happens with Niko that reveals some of Hirayama’s complex backstory. For the first time, we see him weeping.

In another scene, Hirayama is approaching Mama’s restaurant. Through the large window, he sees Mama hugging another man. Distraught, he heads to the river and smokes a cigarette. I don’t want to reveal too much, but what happens next is quite moving. After feeling as if I’d been Hirayama’s close companion for many days, I resonated with the character and experienced those emotions alongside him. The last few minutes of the movie brought me to tears—a testament to Koji Yakusho’s phenomenal acting and Wim Winder’s nuanced directing.

The lush and soulful soundtrack adds an engaging texture to this film. Hirayama owns a collection of old cassette tapes and plays one on his way to work each morning. The film’s title comes from the Lou Reed song, Perfect Day. He listens to other classics such as Van Morrison’s Brown-eyed Girl and Nina Simone’s Feeling Good. This Faulkner-reading guy who listens to American classics erases any stereotypical view you may have had regarding people who clean toilets for a living.

Once I relaxed into the rhythm of the film, I became thoroughly engaged by the great acting, gorgeous cinematography, and the moving soundtrack. Most of all, the central message of the movie has had a lasting effect on me: to be happy with what is given to you.

Almost daily, I’ve been reminded of the film. I think of a line, an image, a bit of dialogue, and especially Hirayama’s joyful embrace of mundane aspects of his life. Originally, Wim Wenders intended to make a documentary about the splendid and innovative public toilets of Japan, but somewhere along the line, he decided to create this film instead. I am very glad that he did.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Sounds like a movie that Chris and I would like.