Our House in the Cornfield

(First published in The Blue Nib Journal. Re-printed with permission.)

For four years, I lived in a little white Cape Cod perched atop a bluff above Johnson’s Cove on Aspinook Pond, a small body of water that spilled out of the Quinnebaug River. You can locate the exact site on any good map of Connecticut. I had joined VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), a branch of the Peace Corps. I’d rented the house with John and Sheila, two other VISTA volunteers. I worked with troubled teens, wards of the state who had been committed to a psychiatric hospital. Most of my 17-year-old patients had behavioral not mental health problems and were warehoused at the facility as they waited to turn 18, at which time the state would deposit them on the curb. My job was to “de-institutionalize” them before that sad day. Despite my optimism, passion and hard work, no one became de-institutionalized and no one was adequately prepared for emancipation day. John and Sheila worked at a legal aid office as an attorney and paralegal, respectively, advocating for clients with benefit and housing issues. All three of us staggered home at the end of the day, exhausted from our emotionally draining jobs.

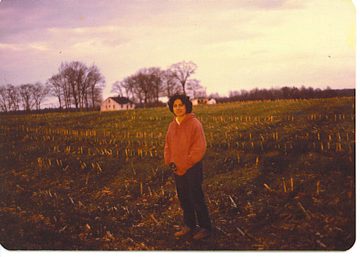

The Arpins, a French-Canadian family, had owned the fruit and vegetable farm before we moved there. To get to the property, you’d have to drive through Jewett City, head down route 12 for a while, then turn onto a steep gravel road. On either side of the narrow lane stood a ten-acre cornfield. A careless farmer rented the field. Possibly, he was drunk as he sowed the seed. Raggedy stalks leaned against each other in chaotic rows. He rarely remembered to gather his harvest. The only time the fields looked impressive was the end of the summer when the dense green wall of stalks and tassels obscured the random rows. In August, we’d pick the ears and shuck them as we ran toward the house. Then, we’d plunge the corn into boiling water for exactly six minutes. My mouth still waters at the thought of their sweet deliciousness.

A quarter mile down the road sat the house, dwarfed by the huge oak and maple trees growing alongside it. In the spring, the grassy field and the steep hillside behind were awash in color: first the crocuses, then narcissus and daffodils. Later, several rows of peonies bloomed. Too bad we never remembered soon enough that peonies needed to be supported. The first stiff breeze toppled them, scattering blossoms, a crazy quilt of color.

If you walked south from the house along the ridge above the water, you’d come across a tangle of raspberry canes. Each fall, we’d tried to prune the dead cane, but never got far, our interest waning as the thorny branches shredded our wrists and hands.

Beyond the raspberries stood huge blueberry bushes, at least fifty plants, all taller than I. Birds stole most of the raspberries, but the blueberry bushes stayed loaded with fat berries. We made pies, jellies, jams, cobbler, poured them on our Cheerios, once threw them in salad (yuck). When I was unemployed after my VISTA stint, I sold them from a folding table set up alongside Route 12.

Adjacent to the blueberry patch, we grew a vegetable garden. After we tilled a large rectangular area, we planted tomatoes, peppers, carrots, lettuce, green onions, beets, radishes, and marigolds. Hoping to keep insects away, we sprayed the plants with a castile soap/hot pepper mixture. The bugs did not depart, but the pepper spray burned our eyes and made our fingers red. To keep the furry pests out, we fenced off the area with posts and chicken wire.

Chicken wire did not block entry to the local groundhog, nor to a family of star-faced moles. We never figured out how to combat the moles.We wanted that groundhog dead, but we were squeamish about doing it ourselves. So, we asked for help from our friend, Michael, who was preparing for the LSAT’s at the time. One day, Michael sat in the hot sun, a law review book in hand, with a .22 rifle across his lap, and waited for the groundhog to appear. From the house, late in the afternoon, we heard one shot, then another. Michael came into the kitchen and reported his success. Still squeamish, we did not walk out to corroborate.

Heading further south along the ridge above the cove, a well-worn path led to a tiny cemetery. Several gravestones lay broken at the edge of the field. All were illegible, except for one. You could barely make out the words, “Capt. Ambrose Pierce, 1779…” I made many visits to Captain Amby. I’d lie in the grass by his lichen-covered stone. I’d tell him my various woes, mostly concerning the terrible situations of my patients at the mental hospital.

On the backside of the cemetery, a huge chunk of land had eroded way, making a U-shaped indentation in the hillside. Judging from the pattern of the headstones, we assumed some had wound up in the water below. John and I once paddled a canoe to the area then poked long sticks into the muddy water, looking for broken markers.

We found no gravestones but noticed a large wooden chest floating below the cliff. We dreamed of the treasures that might be contained within. The ancient Egyptians would have envied our technique for dragging that chest up the steep incline. First, we tied a thick rope around the handle. Then, as well as we could from the canoe, we eased the chest onto the narrow strip of shore. John disembarked and clambered straight up the hill with the thick rope tied around his waist.

I paddled back to Johnson’s Cove, climbed the path, and ran across the field to the cemetery where John had set up a mini-pulley system. I don’t remember the details of how we got it up the hill, but I do know we had sore backs that night.

Once home, we forced open the clasp, hoping to find gold coins or at least a few soggy dollar bills. Instead, we discovered, saddle soap, bridles, saddle oil, rags, and other small metal items we couldn’t identify—horse toenail clippers? Do horses have toenails? Both of us being from a small city, New Britain, John and I had no idea.

We found a name and address glued on a card inside the case. When we called, a gruff man said that the previous Saturday night, his pick-up truck had gone off the bridge over the Quinnebaug. Heavy drinking might have been involved. He didn’t provide any details except that he managed to swim ashore. His truck had been pulled out, minus the tack box. Grumpy came by the next day. We were broke and hoped for a small reward. He didn’t offer us one, so we kept the saddle soap. I’m not proud of that.

One year, that same careless corn farmer planted a field of tall reed-like grass. Once again, the man never did anything with it. Sheila was a weaver. Our attic was filled with her enormous loom, rows and rows of threads at one end, a beautiful, patterned cloth at the other. She had been reading about Native American basket weaving. So, late November, she and I built a simple loom, constructed out of branches and twine. After about two days’ labor, we had woven a reed mat, about six by eight feet in size. I have it in my garage to this day.

Between two large trees near the house, we’d strung a wide hammock made of rope. In theory, it was a shady place to spend a blistering summer afternoon. Many of our friends enjoyed resting there. I could never get the hang of getting in and out without tipping onto the grass.

Near the hammock, we kept a weather-worn picnic table with a splintery bench on either side. Summers, we hosted huge gatherings, picnics for everyone we knew, their children, their parents, their pets. We’d set up volleyball, croquet (minus one wooden stake and with bent clothes hangers for hoops) and rent canoes to paddle on the pond. One time, a couple boys who were playing with lit marshmallow-making sticks, set the cornfields on field. A guest ran into our house, pulled the cover off my bed, and tried to smother the fire. The oversized yellow and white woven cotton blanket had been my grandmother’s. The man only succeeded in fanning and spreading the fire as the blanket billowed up and down. Ultimately, the Jewett City fire department came out, doused the blaze then gave us an incoherent fire safety lecture. My blanket sustained many burn holes. Despite many washings, the smell never left it.

You could enter our home only through the back door and had to cross a long wooden walk elevated above the ground. The walk ran along steep hillside directly over the cove. All in all, it felt as if you were entering a treehouse. A front door existed but it was jammed shut. Our landlord refused to fix the door and we lacked the both the initiative and skills to do so. The only time this mattered was a day when I was home sick from work. Dressed in my pajamas, I walked into the kitchen to see a burglar carrying our stuff up the steps from the cellar. He’d already piled many of our belongings outside on the wooden walkway—a pathetic collection of old record players and speakers. We owned little of value. My first impulse was to run, but the scraggly young man happened to be blocking my only means of egress. I briefly considered trying to push him down the stairs but wasn’t positive I possessed the heft to manage that. Instead, bizarrely, I said, “You must be from the quarry next store. You must need to use my phone. Go ahead.” Equally bizarrely, he pretended to use my phone, then quickly left. I called the police who were not interested enough to come out since he hadn’t taken anything.

From the wooden walkway, we had a gorgeous view of the pond and open sky above it. Sunsets took my breath away. Sometimes we’d clap while watching particularly spectacular display of color. One night at sunset, the whole sky was filled with rows of vertical blinking red lights, from the horizon straight on up. They were still and definitely not planes or jets or like anything we’d ever seen before. The hair on my arms stood up. I phoned a policeman who lived down the road. The sight impressed him. He called the station where his colleagues were befuddled. The next day an article discussing the phenomenon appeared in the newspaper. Apparently, many in the northeast part of the state had seen the lights. No one had an explanation. I figured they were aliens. Honestly, I did. At the time, it’s what made the most sense to me.

Mid-winter the pond and sometimes the river would freeze over. One January night, well after midnight (only one of us had a day job at that point) we were skating along the river. When ice is thoroughly frozen, it makes deep groaning sounds. We imagined the sound was the bellowing of trapped whales begging to be rescued. As we headed home, we noticed that the northern horizon flamed with dancing lights—blue, yellow, purple, sparks of orange. I assumed we were viewing the beginning of a nuclear holocaust or maybe that the aliens had made a return trip. But John had paid attention in his science class. He said, “Northern lights.” I’d never seen such celestial majesty and ever since have yearned to view them again. I’m counting on there being Northern Lights in heaven.

If you walked north away from our house, you’d soon come to a quarry. I don’t remember the kind of stone they pulled from the earth, all I remember are the high cliffs of sand. In the summer, on Sundays, when the quarry workers were not around, we’d amuse ourselves by jumping off some of the moderately high piles into other sand piles below. I especially loved that half-second sensation of buoyancy as I dropped. One January, on Superbowl Sunday, we were hiking around the quarry. Everybody else had climbed down the sand hills and they were heading back toward the house. Kick-off would be in a couple minutes. I don’t remember why, but I lingered on top of one of the sand hills, not the biggest one, maybe fifteen feet off the ground. I forgot it was January. I forgot the ground was frozen. All I could think about was not missing the kick-off. So, I leapt from the little cliff, thinking I’d land in nice cushy sand. When my feet hit the frozen block of sand, I felt a sharp pain run up through both legs and into my spine. Later, x-rays showed that I had cracked both heels. I spent the next several months on crutches.

Let me take you inside the house. The wooden walkway led to a side door which opened into a tiny sun porch. With windows on three sides, the room offered a lovely view of the cove and the pond beyond. Plants, in various stages of death and dying, filled the room. Sheila loved plants, in theory. Invariably, though, she’d forget to water them or would neglect to take them in on chilly nights. Always the optimist, Sheila started one plant after another from seedling. One plant stands out in my memory: a large brown oval entity with two thick ridged shiny leaves growing out from either side. We named it The Alien Tongue. Amazing all of us, including Sheila, The Tongue once managed to produce a gorgeous pink blossom despite its abject living conditions.

From the sunporch, you’d walk into the dining area, a little alcove with two sides of windows. We spent many hours, laughing, talking, and eating at the round wooden table which tilted alarmingly if anyone leaned too hard.

Sheila taught me to cook in our kitchen. We VISTA workers earned a tiny stipend and a monthly allotment of food stamps. Each month, soon after our paycheck and food stamps came in, we’d head to the grocery store. My stomach always growled as we walked the aisles. We’d buy food stamp food: dried beans, cheese, cereal, eggs, and milk. We’d often splurge on a pound of bologna, not waiting until we got home to eat a slice or two. For some reason, we always had an overabundance of eggs. I grew to despise quiche: quiche with broccoli, quiche with spinach, quiche with any leftover rotting in the recesses of our refrigerator. I wanted steak quiche or at least bacon quiche, but our budget didn’t allow for such extravagance.

On one special occasion, John attempted to make beef bourguignon using an old and, in retrospect, defective pressure cooker. John had spent a small fortune on the ingredients. He planned to feed several friends with the meal.

The pressure cooker blew up, spewing chunks of pink goop on the ceiling, walls, and floors. Clean-up took hours. At first, the kitchen smelled like a winery, overwhelming, but not a bad fragrance. However, after a day, the odor shifted, stinking like the bottom of a trash can at a fraternity house on a Sunday morning.

An old upright piano stood in one corner of the sunken living room, a surprise present to Sheila and from John and me. I never got beyond picking out songs one note at a time. Sheila played a few simple tunes. But mostly, the piano sat untouched, used as a wooden plantstand for Sheila’s expiring flora.

A large brick fireplace took up the central wall of the living room. We built a fire almost every night from late September through to the cool nights of March. Our television, with its coat hanger antenna, pulled in two stations at best and usually only one at night. The reception was unpredictable. Late at night, we’d watch Monty Python re-runs. We’d shout, “Doctor, my brain hurts.” We’d bravely say, “It’s merely a flesh wound.” Or we’d chant, “Spam, spam, spam, spam.”

Capricious reception made television an undependable source of entertainment. So, we mostly sat by the fire, telling stories, singing, and nodding off. Some mornings I’d find myself chilled and achy, curled up by cold, gray ashes.

My bedroom, when I bothered to go to it, was in the unheated attic which I shared with Sheila. You entered my room through a pale green door on the left side of the stairwell, a snug space under the steep eaves of the house. A person of normal height, standing up straight, would have to confine herself to a two-foot square area in the middle of the room. Fortunately, I am short and didn’t bonk my head as frequently as most people might. The attic felt bitter cold all winter. I slept in a hooded sweatshirt, sweatpants, and socks. Many mornings, I awoke to see my breath hovering in the air. A village of black mice lived under the eaves, too. I’d sleep with one eye open as they scuttled through the room at night.

Sheila occupied the open space above the main living area of the house. No door, so it wasn’t exactly a room. Her ceilings were higher, and the room was larger than mine, although much of it was taken up by her loom.

John had the back bedroom downstairs. From a bay window in his room, he enjoyed a beautiful view of Aspinook Pond. He also enjoyed another advantage, the only bathroom in the house was right outside his door. I coveted his bedroom, especially in the middle of cold nights when I’d have to make a trek to the bathroom from the icy attic.

We never had much money, so sometimes we bartered goods. Sheila traded her battered VW beetle for a couple of cords of wood. The car hadn’t started for a long time and a family of squirrels had taken residence in it. So, as trades go, it wasn’t an unwise one. However, I traded my Pontiac Tempest for a wringer washing machine—the worst deal of all time because my car still worked, more or less. Plus, we didn’t know we had to ground the washer. One day, I had a hand on the machine and the other on a metal sink, completing a magic electrical circuit that delivered a jolt to my body which sent me sailing a few feet. I experienced weird aches and pains for weeks.

We lived in the house four years, four years of dinners, fires, walks in the woods, huge parties, and picnics. Eventually, John moved to a little cabin, up the road and across the river. I headed off to Dartmouth to start graduate school. Sheila found an apartment in a nearby town. At some point, John and Sheila started dating. After a slow and steady courtship, they were married. Although Sheila already had four of her sisters in the wedding party, she asked me to be a bridesmaid, too. I felt grateful and honored. In September, almost exactly a year after their wedding, Sheila was a bridesmaid at my wedding to Bruce in Hanover, New Hampshire.

I tend to idealize those four years we had together, not many worries except for an extreme lack of cash. Life was amazingly simple, no cell phones, no computers, no internet, and an undependable TV. To communicate with someone, you wrote a letter, phoned, or visited. No entertainment in Jewett City, except for lovely woods and gorgeous waterways. We worked hard and played hard with VISTA colleagues and other friends in the area. I learned how to cook, paddle a canoe, carve a spoon out of an apple branch, make blueberry jam, build a loom, weave a mat, chop wood, keep a fire going and boldly sing with friends regardless of how it sounded. And, after a lovely four years, I learned how to let go and move on. But not completely. John, Sheila and I are still the best of friends to this day.

(Photo by Jen Fariello)

Deborah Prum, author of many short stories, has won thirteen awards for her fiction, which has appeared in The Virginia Quarterly Review, Across the Margin, Streetlight and other outlets. Her essays air on NPR member stations and have appeared in The Washington Post, Ladies Home Journal and Southern Living, as well as many other places. Check out her WEBSITE. Check out her PAINTINGS.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

It sounds like you were very happy during those four years. What a nice memory!

What lovely writing. Thank you for sharing that part of your life, Debby.

Thank you so much.